To understand this question, it’d be helpful to first think about a much older revolution in payments technology. . . cash.

Super-Cash!

Cash has an obvious, yet extraordinary super-power. I can hand it to anybody near me and value will be transferred instantly, directly, peer-to-peer, person-to-person. Settlement, with finality, using central bank money. And nobody else need know. And nobody can stop me.

But this super-power only works at close distance. If I want to transfer value to somebody in a different town or in a different country, I need to trust other people. Sure: I could put the cash in an envelope and post it. But even then I’d have to trust the postal service.

Or I could use a bank. But I’d be trusting them to be good for the money. And I’d have handed over control: if my name’s on the wrong list, the bank would be obligated to seize my funds. And if you’re on the wrong list, the bank will refuse to transfer the money to you…

This is because “digital” money is not the same as physical cash.

And the world’s financial plumbing—payments systems, correspondent banking, SWIFT, etc.—is a direct consequence of this observation: physical cash really is fundamentally different to every other form of money: only physical cash is a bearer instrument. And only physical cash can be transferred without permission – censorship-resistant.

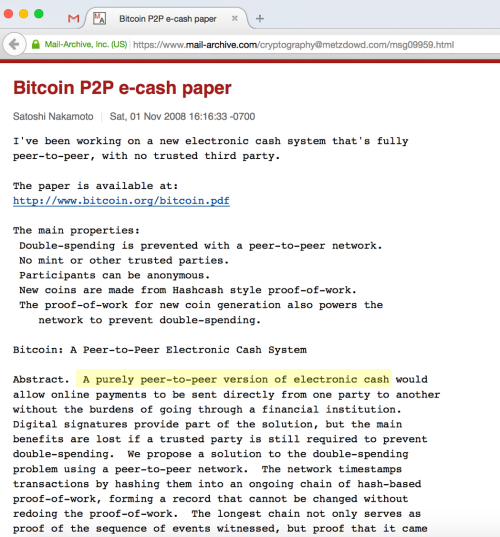

Or so we thought until Bitcoin. A curious email to an obscure cryptography mailing list at the end of 2008 said something quite audacious. The email, from the hitherto unknown Satoshi Nakamoto heralded the arrival of Bitcoin and the advent of “purely peer-to-peer electronic cash”.

We all know the story of what happened next.

Except… what many people have missed is that the choice of the word “cash” in that email was absolutely critical and absolutely deliberate. What this email announced was the arrival of a digital bearer asset that is censorship resistant. Digital cash. A digital asset that you can hold outright, with no risk of confiscation, and which you can transfer to anybody you choose without permission from anybody else.

And the funny thing is: the architecture of Bitcoin flows almost trivially (almost…!) from this requirement. Proof-of-work, the peer-to-peer network, mining, the mining reward, the blockchain. The lot. It’s as if the genius of Bitcoin was to ask the question.

But why say this in 2016? This exact same thing could have been said at any point from 2009 until now. There’s nothing new here. Except, nobody asks the obvious question:

Who actually wants a censorship resistant digital bearer asset? Well… some people do, of course. But none of them are banks or corporates. At least, I’ve not yet met a bank that wants this. So why are so many banks, corporates, VCs and startups spending so much money in this space?

I think there are two completely distinct reasons and that the world of “blockchain technology” is actually two completely different worlds—the world of bitcoin and the world of banks. Each has different opportunities and different likely winners, and those who don’t realise this might be about to lose a great deal of money. So let’s look at these two worlds one at a time.

The World of Bitcoin.

We should probably be realistic here. Bitcoin is not the solution to Greece’s crisis and it won’t immediately bring finance to the world’s poor. But it turns out that censorship resistance is extremely valuable, even for people who don’t think they need it.

Because censorship resistance implies openness, it implies permissionless innovation not just permissionless use. Anybody or anything can connect to an open network like Bitcoin to own and transfer value. And anything that is open, standardized, owned by nobody, and useful smells very much like a platform.

And, as with the PC or the Internet, we’ve seen how those stories about open platforms tend to play out: without a gatekeeper even the scruffiest of garage-based inventors gets a chance to share their idea with the world. And even if only one in a million scruffy inventors ever has the genius and the luck to be a Jobs, Gates, or Musk, we can all expect to benefit massively from the freedom that an open platform provides.

But notice something else: Bitcoin is worse than existing solutions for all the use-cases that banks care about. Openness has a cost. It’s expensive. It’s slow. And it’s “regulatorily difficult.” And this is by design.

So this makes it doubly interesting. Because it means Bitcoin is probably worse than existing solutions for all the things most firms care about but vastly better for one single use-case (open access to value transfer) that could be very useful for some people–especially innovators.

Isn’t that pretty much the definition of a disruptive innovation? Something that’s worse for existing use-cases but solves a niche use-case very well? So, if this is true, we should expect to see adoption of Bitcoin come from the margins, solving marginal problems for marginal users.

But disruptive innovations have a habit of learning fast and growing. They don’t stop at the margins and they work their way in and up. So this is why I think so many of the big-name VCs are so excited about it.

So the incumbents should be keeping a very close eye on what’s going on. If anything in this space is going to disrupt them, it will probably come from this world. But it’s perfectly understandable that vanishingly few of them are actually engaging deeply in this world.

So if Bitcoin isn’t why banks are looking at this space, what are they looking at? How have so many people convinced themselves that there is something of interest here that is “separate” to Bitcoin or systems like it?

At this point, it’s customary to observe sagely that “of course, the real genius of bitcoin was the blockchain; that’s where the value is”. But I’ve discovered something rather amusing. If you push the people who say this, and ask them what they actually mean, most of them can’t! And yet… whether they understand why or not, they are actually on to something.

It comes down to how bitcoin delivers on the design goal of “censorship resistant” cash. Imagine Bitcoin didn’t already exist and you were asked to design a system of censorship-resistant digital cash. How would you do it? Well… you couldn’t build it around a central database: it could be shut down. That doesn’t sound very censorship resistant. And you couldn’t rely on a network of trusted people around the globe since they could collaborate to block your transactions. And in any case, who would control the identity system that helped you be sure these people were who you thought they were in any case?

It turns out that the answer is quite unexpected… and it’s something I’d bet almost all engineers would consider completely mad. The answer is that you get everybody who fully participates in the system to maintain a full copy of the ledger. And every time somebody, anywhere in the world, spends some bitcoin, we’re going to inform everybody who’s maintaining this ledger and they’re going to store a copy of that transaction too.

Bitcoin essentially runs on a massively replicated, shared ledger. (The trick is in keeping it consistent, of course…) It sounds insanely inefficient and expensive, and perhaps it is. But we also have to ask ourselves: inefficient and expensive as compared to what?

And this leads us to the other world.

The World of Banks

Just look at the state of banking technology today—payments, securities, derivatives… pick any one. They all follow the same pattern: every bank has built or bought at least one, usually several, systems to track positions and manage the lifecycle of trades: core banking systems, securities settlement systems, multiple derivatives systems and so on. Each of these systems cost money to build and each of them costs even more to maintain. And each bank uses these systems to build and maintain its view of the world. And they have to be connected to each other and kept in sync, usually through reconciliation.

Take even the simplest OTC derivative contract: it is recorded by both sides of the deal and those two systems have to agree on everything for years. Very costly to operate.

But what if these firms—that don’t quite trust each other—used a shared system to record and manage their positions? Now we’d only need one system for an entire industry… not one per firm. It would be more expensive and complicated to run than any given bank-specific systems but the industry-level cost and complexity would be at least an order of magnitude less. One might argue that this is why industry utilities have been so successful.

But a centralized utility also brings issues: Who owns it? Who controls it? How do the users ensure it stays responsive to their needs and remains cost-effective?

The tantalizing prospect of the blockchain revolution is that perhaps it offers a third way: a system with the benefits of a centralized, shared infrastructure but without the centralized point of control: if the data and business logic is shared and replicated, no one firm can assert control, or so the argument goes.

Now, there are lots of unsolved problems: privacy, performance, scalability, does the technology actually work, might we be walking away from a redundant (antifragile?) existing model? Who will build these platforms if they can’t easily charge a fee because of their mutualised nature? Difficult questions.

But see: this has nothing to do with funny internet money, bitcoin or censorship-resistant digital cash. It’s a completely different world.

Two Revolutions for the Price of One

The blockchain revolution is so fascinating because it could actually be two completely different revolutions… both profound in their implications:

Censorship-resistant digital cash providing a new platform for open, permissionless innovation driven from the margins. And industry-level systems of record driving efficiencies for incumbents.

Neither of these are “sure things”… they are both high risk speculative bets… but they’re also very different bets.

Richard Gendal Brown is Chief Technology Officer at R3 CEV. The views shared here don’t necessarily represent R3’s positions, strategies or opinions.