Is Bitcoin a Security?

Today we are releasing our Framework for Securities Regulation of Cryptocurrencies. In it we lay out the case for treating some cryptocurrencies as securities—and some not.

Today we are releasing our Framework for Securities Regulation of Cryptocurrencies. In it we lay out the case for treating some cryptocurrencies as securities—and some not.

Strange bunch of things right? Mink, bullion, golf course, diamond, worm farm, chinchilla, orange grove, beaver? Aside from the anomalous prevalence of furry mammals, what can we say about this random grouping of. . . things?

They can all be classified as securities when sold as investments.

And yes, in those cases, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission can regulate investment contracts for these odd things—just like they would regulate AAPL, GOOG, or MSFT.

With that context in mind, it should be less surprising to learn that, yes, there’s a provocative argument that Bitcoin investment might also be within the SEC’s jurisdiction (if mink, then why not doge!?). To address these open questions, today we are releasing a new Coin Center Report, ourFramework for Securities Regulation of Cryptocurrencies. In it we lay out the case for treating some cryptocurrencies as securities—and some not.

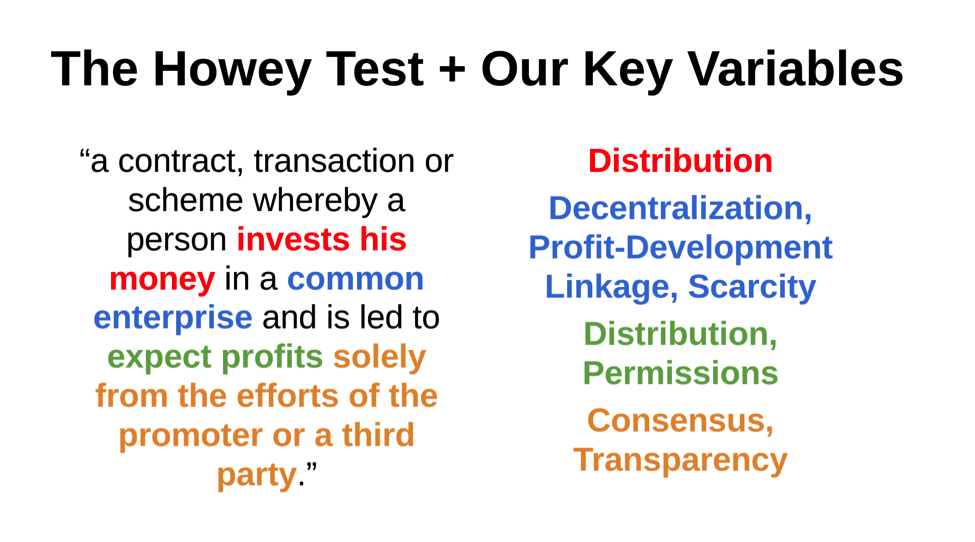

The framework is based on the Howey test for an investment contract—which comes from a famous case about orange groves—as well as the underlying policy goals of securities regulation. We find that several key variables within the software of a cryptocurrency and the community that runs and maintains that software are indicative of investor or user risk. These variables are explained in depth—we manage to discuss everything from proof-of-burn to sidechains to pre-mining to GitHub—and then these variables are mapped to the four prongs of the Howey test in order to create a framework for determining when a cryptocurrency resembles a security and might therefore be regulated as such.

We find that larger, more decentralized cryptocurrencies (e.g. Bitcoin), pegged cryptocurrencies (i.e. sidechains), as well as distributed computing platforms (e.g. Ethereum), do not easily fit the definition of a security and also do not present the sort of consumer risk best addressed through securities regulation. We do find, however, that some smaller and questionably marketed or questionably designed cryptocurrencies may indeed fit that definition.

The framework is actually pretty simple, and there’s a summary of it below.

An investment contract for purposes of the Securities Act means a contract, transaction or scheme whereby a person . . .

And we explain some seven key variables that might differ from one cryptocurrency to another:

And then these variables are mapped to the Howey test to determine when a given cryptocurrency sale would look like investment contract, and might be wisely regulated as such. That matching looks like this:

And after discussing these variables, we offer the following policy recommendations:

So, if this is an area of law that you’re interested in—or if you are developing ChinchillaCoinz—you’ll probably want to read the full report to get a good sense of how it all works.